During the US presidential election campaign, Donald Trump promised to fix the economy by eliminating inflation, cutting taxes and increasing tariffs. This raises a challenge for asset allocators as to how these policies will hit expected asset returns in the short and long run.

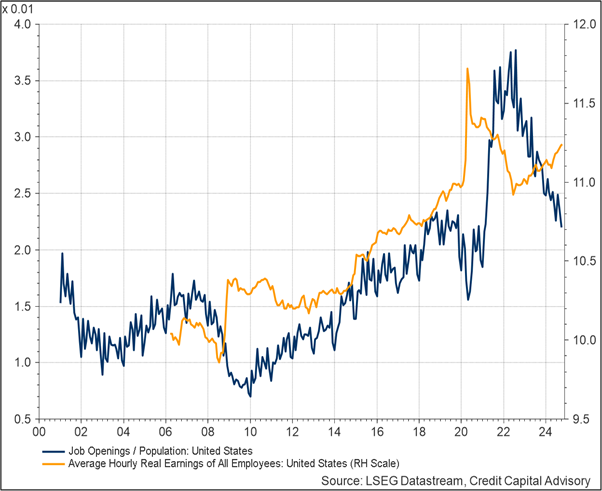

The incoming president will inherit a robust economy with a labour market in rude health and unemployment at only 4.1%. Real wages are rising and job openings, although down from post-pandemic levels, are still at the same highs reached during 2018-19, as shown in chart1.

Chart 1: US Labour Market Indicators

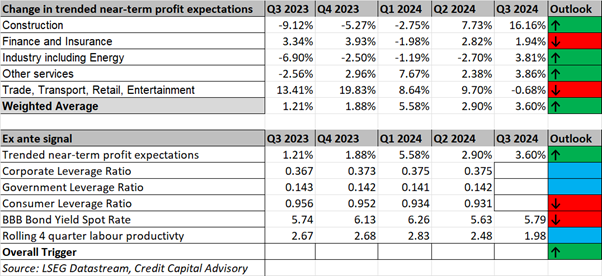

Furthermore, the ex-ante return on capital across the US economy is expected to keep increasing across most sectors although Trade, Transport, Retail and Entertainment appears to have peaked due to slowing consumer activity. The corporate leverage ratio has also levelled off indicating less expected future consumption growth, as noted in table 1. Hence there is likely to be a deceleration in profit growth over the coming quarters.

Table 1: US Summary Ex Ante Signal

This limited consumer upside could theoretically be boosted if Trump was indeed able to eliminate inflation, however, there is very little chance that Trump will be able to achieve this, for a number of reasons.

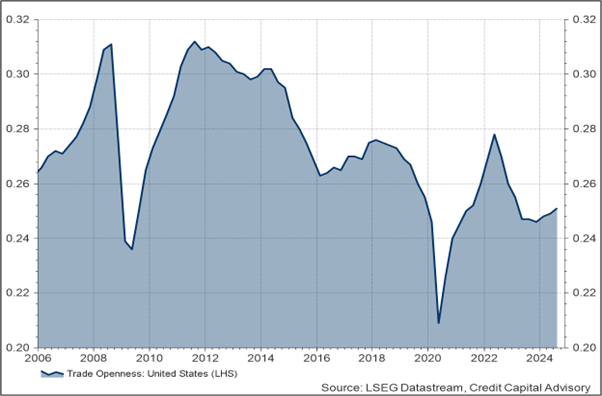

First, inflation dynamics within a country are impacted by the level of integration into the global economy. When China, India and Eastern Europe entered into the global trading system in the 1990s, firms exploited these lower cost locations, placing downward pressure on nominal wage growth in developed markets, particularly for low and medium-tech manufacturing where unions once had significant bargaining power. Hence, the greater trade openness, the less impact this will have on the rate of change in prices. Conversely, more closed economies will tend to be more inflationary. This effect can be seen in the changing nature of the Phillips Curve through time with a more globalized economy demonstrating flatter slopes as noted here.

Trump is of course committed to reducing trade openness by introducing tariffs as a way of trying to put US firms on a “level playing field.” But this comes at a time when the level of trade openness in the US economy is already back at 2006 levels. As the US economy becomes more closed in conjunction with tight labour markets, the economy is likely to become more inflationary, not less.

Chart 2: US Trade Openness

Second, Trump’s desire to remove millions of illegal immigrants, who comprise about 5% of the workforce, will further increase inflationary pressures in what is already a tight labour market. The extent to which this will impact inflation, however, will also depend on Trump’s policies on legal immigration – which in principle could counteract this effect.

The outcome of Trump’s policies is that rather than eliminating inflation, the rate of change of prices is more likely to rise, anchoring towards 3% rather than the “steady state” 2.5% – 3% band Credit Capital Advisory forecast in 2023. This assumes that legal immigration is able to largely counteract the removal of illegal workers.

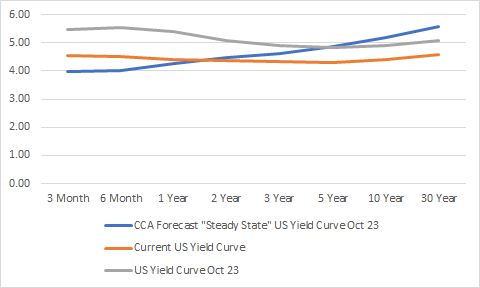

The impact of this marginally higher level of inflation will be to further strengthen a rise in longer term interest rates with only limited downside at the short end. This is unlikely to fundamentally change the “steady state” shape of the yield curve forecast last year as noted in chart 3.

Chart3: US Yield Curve Forecast

Source: LSEG Datastream, Credit Capital Advisory

The future path of interest rates for the Trump administration is that long term rates are likely to rise by at least another 50 bps. As noted in chart 4, one and two year rates are already close to steady state levels, while very short term rates will come down a little further. However, higher long term rates means financial products such as mortgages are not going fall back to the levels consumers have gotten used to since the 2008-2009 financial crisis; indeed they will become slightly more expensive than they are now.

Given that long term rates are likely to settle over the 5% level, consumers will need to start making adjustments in their behaviour to this new bond market regime. This of course will impact future consumption and further slow the economy, thereby placing downward pressure on capital values.

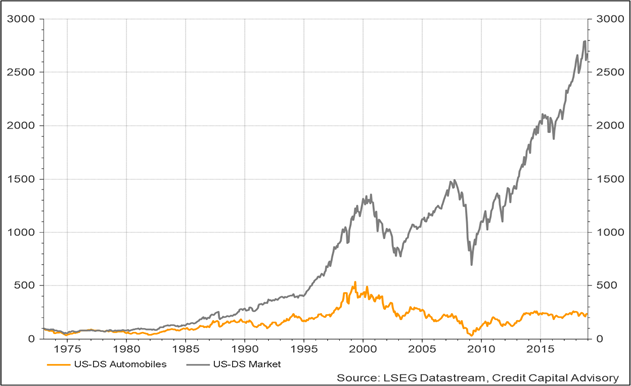

In conjunction with this expected slowdown in consumption, the impact of tariffs on US firms will make them less competitive, less innovative and therefore less profitable which will negatively impact capital values. During the 1970s, US automakers struggled to compete with imported Japanese cars which US consumers thought were better and cheaper, thereby leaving the big three in Detroit reeling. This was exacerbated when Japanese firms began manufacturing in the US to avoid the Voluntary Export Restraint limits imposed on Japanese auto firms in 1980. As is shown in chart 4, 1980 marked the beginning of the disentanglement of the US auto sector’s performance from the overall performance of the US stock market. Investors who bet on uncompetitive US auto firms did not do very well.

Chart 4: US Auto Sector vs Total US Market

The challenge for investors is where else should they put their money at the moment? The eurozone is still struggling to grow. Although the new UK Labour government inherited a growing and more confident economy, the government’s doom-mongering and recent budget which increased labour costs for firms, is unlikely to engender greater interest in the UK stock market from international investors, particularly since it became an international pariah in 2016. Profit expectations, though, are still up.

Hence, for the next quarter, the broader US equity market will likely remain the destination of choice for investors. Even if long term interest rates rise more quickly than anticipated, the continued robustness of the economy is unlikely to lead to a jump in defaults, which would negatively impact capital values. However, as lower-rated firms start to refinance at higher levels, it will place further pressure on debt repayments.

Investors can therefore expect some short term gain in capital values, but greater long-term pain as a result of Trump’s economic policy. Consumers will finally have to accept that there has been a structural shift in the long term cost of money and rein in their spending, while firms may become increasingly uncompetitive protected by high tariffs.