US equity investors in the six year period between 1973 and 1978 would have made no nominal return on their investment, with inflation averaging 7.7%. Hence it is understandable that investors remain so concerned about the potential impact of a higher rate of rising prices. This is why all eyes are currently on the bond market to see whether it is signalling a return to the 1970s, and to understand if firms are able to maintain and grow profit margins to service their current levels of debt.

No need to panic

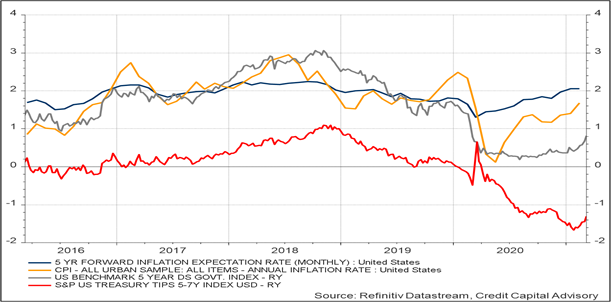

The US February 2021 inflation data showed an increase of 0.4%, resulting in an annualised consumer price index (CPI) rate of 1.7%. The main driver of the CPI remains energy and food, with other items in the index rising at 1.3%. Next month, the rate will increase due to the slump in energy prices last March through June, but these are once-off impacts on the index, which will subside later in the year. Five-year inflation expectations are currently running at 2.1%, as noted in Chart 1.

Chart 1: US Inflation expectations

It has been noted widely though that as consumers emerge from lockdown, supported by government stimulus, the surge in demand for products may not be immediately satisfied, thereby potentially driving up prices.

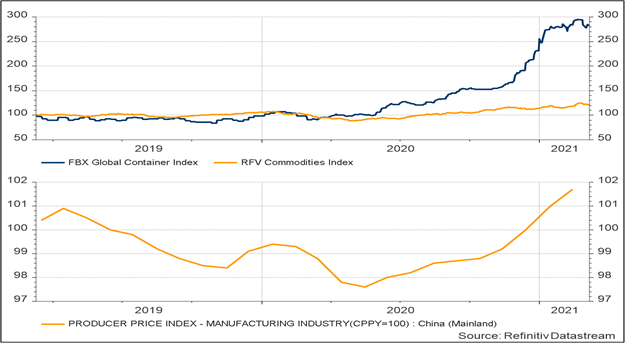

This tightness can already be seen in the shortage of shipping capacity as well as in commodities data which is ticking up as shown in the top pane of Chart 2. Furthermore, the producer price index for manufacturing in China has started to pick up, surpassing early 2019 levels, as demonstrated in the bottom pane.

Such pressures are, however, likely to be temporary given that firms take time to ramp up incremental capacity. Furthermore, the continued low employment participation rate in the U.S. compared to the 1990s and early 2000s, indicates significant slack in the labour force.

Chart 2: Potential inflation indicators

Another reason why inflation is highly unlikely to lead to 1970s-style rates is that the wage price spiral – where rising inflation expectations drove workers to bargain for higher nominal wage increases – took place in a relatively closed economy.

Today, the US economy is three times more open than it was during the 1970s. Greater trade openness places far more downward pressure on nominal wages given that tradeable goods and services can be offshored if wages become too uncompetitive. This also goes some way to explaining the general frustration with globalization from many sections of the electorate.

Chart 3: Annualised change in earnings vs trade openness

Some firms’ profits are bigger than others

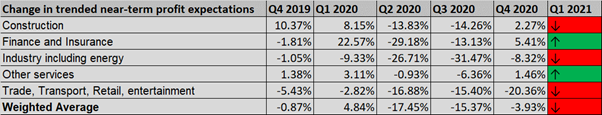

Given that the inflation outlook remains subdued, investors are faced with a further conundrum as equity prices in February bounced back to all-time highs despite the economic slump. The quarterly Credit Capital Advisory dashboard indicates that construction, manufacturing and trade remain negative. The trade sector is likely to be impacted by a massive jump in new business starts, which may dampen future profit growth. On the plus side, financials show robust growth and business services including technology is also showing a slight increase, although the regulatory outlook for big tech remains challenging.

Table 1: Near term profit expectations for the US economy

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Credit Capital Advisory

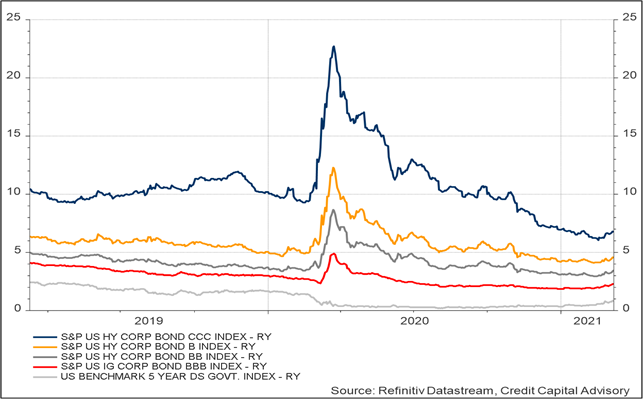

Another issue impacting sectors most affected by the pandemic is the potential jump in expected defaults and hence increase in credit risk. This is something that the bond market has not yet factored into account with CCC spreads reaching record lows in February.

Chart 4: US bond yields by rating band

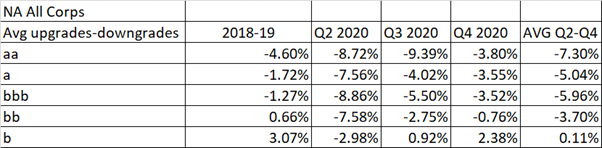

However, the idea that credit risk has been eliminated due to extraordinary monetary policy support does not tally with reality. This can be observed by comparing the relationship between the upgrades and downgrades by banks who have exposure to loans in the North American corporate sector through time.

Using the period of 2018/2019 as a proxy for “normal conditions,” it is possible to observe how the credit risk of obligors has shifted during the last nine months of 2020 based on Credit Benchmark data.

Table 2: North America Credit Transitions

Source: Credit Benchmark, Credit Capital Advisory

During 2018/19 there was a tendency for investment grade names to see a higher number of downgrades to upgrades, while there was a tendency for high yield names to show more upgrades to downgrades. The period between Q2-Q4 2020 shows that the rate of downgrades to upgrades was nearly 3 times higher for a rated obligors, rising to nearly 4 times higher for bbb obligors. Crucially, bb obligors have shown a dramatic level of downgrades compared to “normal conditions” and only minimal upgrade to b. The main reason why b rated obligors are positive is that there is a tendency for banks to churn lower quality names from their portfolios, which by definition results in a slight upward bias in transitions. The upshot of this significant increase in downward transitions will be higher defaults, impacting bond yields and equities in affected sectors.

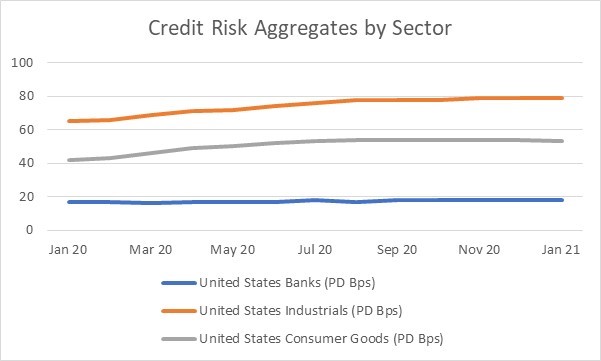

Interestingly though, the credit risk aggregates from Credit Benchmark suggest that the US bank sector can be expected to absorb these losses, demonstrating almost no change in credit risk since the start of the crisis. However, the aggregates also show that US Industrials and US consumer goods have seen a widening in credit risk of more than 20% since the start of the crisis, indicating many firms are struggling with their debt liabilities.

Chart 5: US credit risk aggregates

Source: Credit Benchmark

While investors can be more confident that inflation is unlikely to return to levels observed in the 1970s, this does not mean that all sectors of the market will perform equally as well given the rising expected defaults in sectors affected by the pandemic. Expected profit growth remains uneven, which may well impact relative performance.