Paul Krugman in a recent article argued that the rock star of the recovery – Sweden – has turned itself into Japan. The data he cites to back this claim up is deflation and a halt to the falling unemployment rate.

This is a major claim to make which seems to be derived from the very fact that prices are now falling. However such an analysis falls foul of Scott Sumner’s warning to never reason from a price change. What matters is of course why prices are falling.

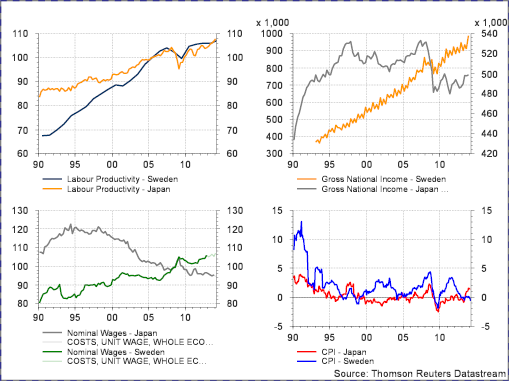

When we compare Japan with Sweden, Krugman is right that Sweden is seeing prices fall – the blue line now is similar to where the red line was from the late 1990s (bottom right pane of chart 1). But that’s pretty much where the similarities end.

Firstly, productivity growth in Sweden has been rising since 2009 whereas between 1990 – 1994 it was stagnant in Japan and it even fell between 1996 and 1999 as shown in top left pane.

Secondly, nominal GDP continues to rise in Sweden whereas Japan’s started to fall from 1994 as shown in the top right pane.

Thirdly, nominal wage growth continues to rise in Sweden whereas in Japan it declined from 1994 as shown in the bottom left pane.

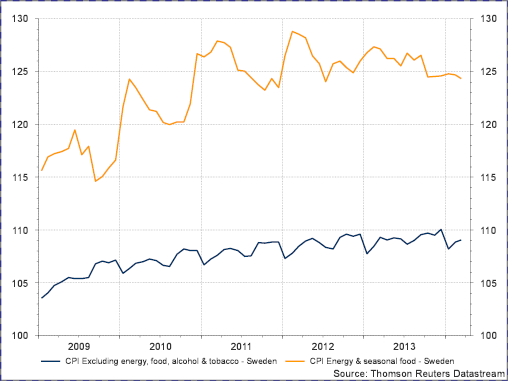

There are however valid arguments that Sweden may well have raised rates too early. NGDP forecast for Q1 2014 from Oxford Economics is down not up. As a result it is plausible that the fall in inflation in Q1 2014 may well be partly explained by a slowdown in nominal income growth. A cursory look at the split between core and headline inflation shows that core inflation has remained on reasonably stable mild upward trajectory, although the recent upward shift from the traditional fall in January price levels appears somewhat sluggish.

Chart 2: Price levels in Sweden

The recent decline in the index itself has come from falling energy and food prices which started to decline in 2012 and continue to do so. However to claim that Swedish monetary policy is entirely responsible for driving these prices down is hard to justify given the numerous other factors that impact this index.