At a conference in 1995, Rex Sinquefield – who set up the first S&P index fund in 1973, quipped that it was only the North Koreans, Cubans and active fund managers who didn’t believe that markets worked. The overwhelming evidence that the vast majority of active fund managers are unable to consistently beat the market has increasingly shifted assets into low cost tracker funds in order to improve returns for savers. However the industry needs to take note that passive funds are also guilty of ignoring market signals, particularly when it comes to mergers and acquisitions. And until the passive industry responds to this, it will remain just as culpable as active managers are in destroying value.

The M&A Problem

In 1999 KPMG published a controversial report on the value of M&A. It stated that 82% of those involved in M&A believed their deals had been a resounding success. However according to KPMG, “only 17% of deals had added value to the combined company, 30% produced no discernible difference, and as many as 53% actually destroyed value. In other words, 83% of mergers were unsuccessful in producing any business benefit as regards shareholder value.” Although the exact figures of the KPMG study are somewhat debatable, the scale of the failure is significant.

Corporate finance theory states that when a public company decides to deploy capital for an acquisition, the information released about the project is then absorbed by the market which then provides a signal as to whether the proposed deployment will create or destroy value. If share prices fall executive teams ought to shelve the project. If they continue with the project, share holders’ should act to protect their investments and vote against the management team. As consultants tend to use these kinds of studies to sell services to improve the success rate of value creation, they have largely ignored the process of signal formation by the market and how these signals get used.

Credit Capital Advisory analysed the infamous takeover of ABN Amro in 2007 by RBS in order to test whether the root cause of the failure might be the market itself. The analysis shows that not only did the market work extremely well in predicting the failure of the acquisition, but that most of RBS’s institutional shareholders including both active and passive investors failed to take any notice of these signals.

Market signals derived from the 2007 bidding war for ABN Amro

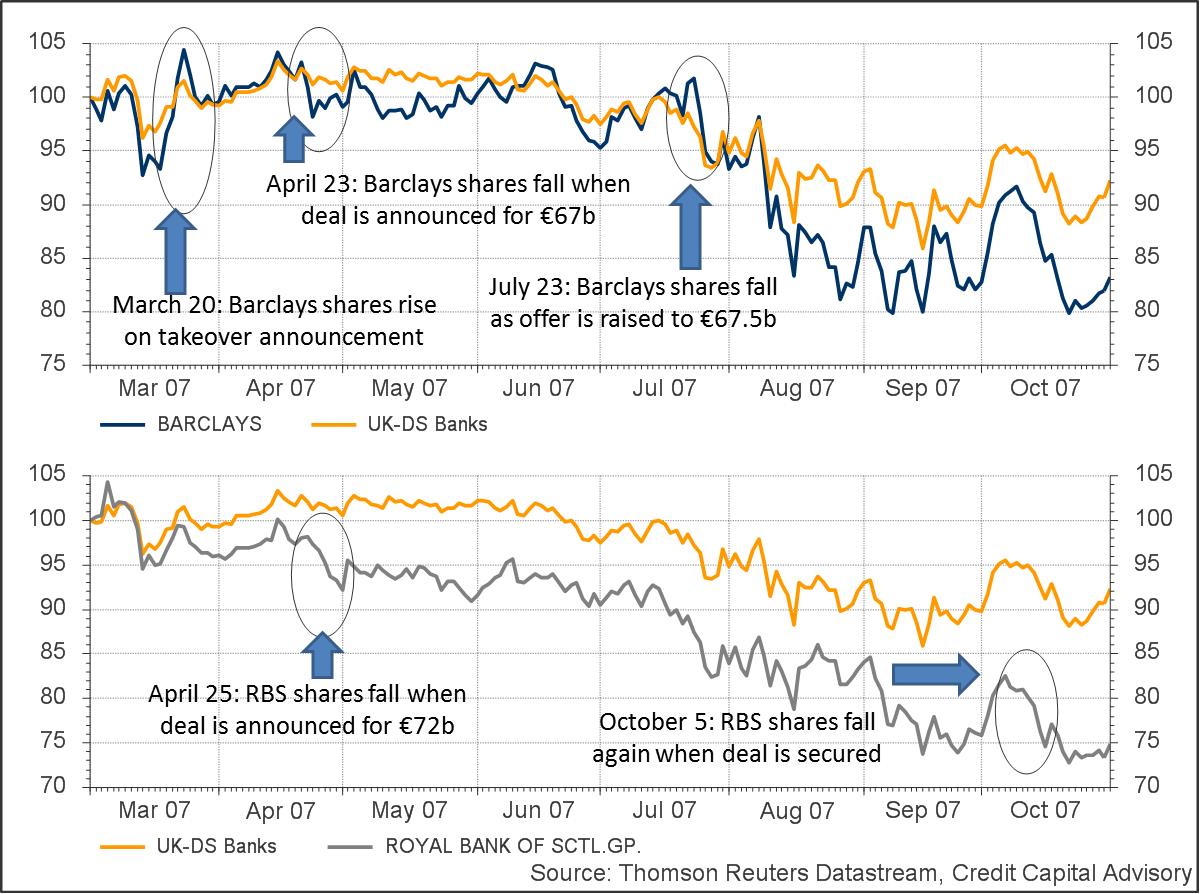

On March 20th it was announced that Barclays and ABN Amro were in merger discussions. As shown in chart 1, Barclays share price rose against the UK banks index as buyers entered the market believing the idea was value creating. The volume data of traded shares is shown in chart 2. On April 23rd Barclays announced its offer of €67 billion causing Barclays share price to fall against the Banks index as the volume of selling increased. Two days later the RBS consortium announced the eye watering offer of €72 billion. RBS shares fell against the index as volume rose to sell the stock. Between April and July, Barclays outperformed RBS, with the market assuming the higher offer was more likely to be accepted. On July 23rd Barclays upped its offer to €67.5 billion resulting in a falling share price against the banks index once more. RBS finally “won” the battle on 5th October as Barclays pulled out leading to a further fall in the RBS share price against the UK banks index and rising volumes as the market sold RBS stock. The RBS share price underperformed Barclays significantly post deal.

Chart 1: Barclays and RBS Share Price against UK Banks Index

Chart 2: Barclays and RBS share prices against volume of shares traded

What’s the incentive to take account of the market signal?

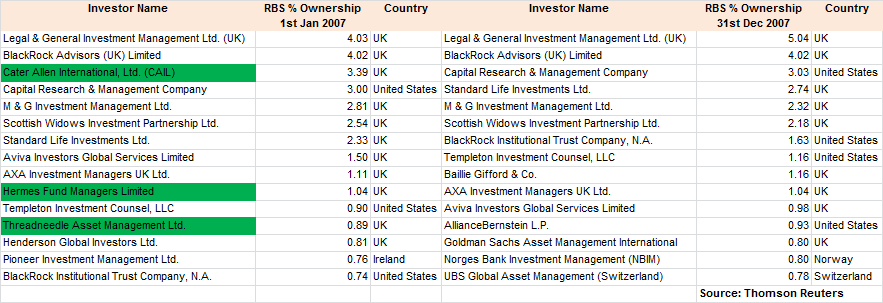

The market signal for the acquisition of ABN Amro by both Barclays and RBS was resoundingly clear. The acquisition was not a very good idea. However according to Reuters 94.5% of RBS shareholders who voted on the acquisition supported the deal. A comparison of the major RBS institutional shareholders using Thomson Reuters data for 2007 highlights the issue at hand.

Table 1: Change in % ownership of RBS of largest institutional shareholders 2007

The data shows that besides the three fund managers highlighted in green who reduced their exposure to RBS by 50% or more, the rest of the major shareholders maintained their tacit support for the RBS management team. Some passive funds increased their shareholdings as part of rising equity inflows, with the rest of the active funds both over and underweighting RBS against the index they were tracking. The fact that some active funds underweighted RBS cannot really be argued to have added much value given what happened to RBS. Thus the view that “at least I didn’t lose as much as the index benchmark” is not a credible one. The market relies on asset managers to ensure that corporate executive teams are not making bad decisions. This is based on the assumption that asset managers would prefer the value of companies to rise rather than fall, so the asset owners whom they are managing the money on behalf of can enjoy a better living standard in retirement. Between 2001 and 2010 the average OECD pension fund barely returned the rate of inflation suggesting that asset managers have not had the same outlook as the owners of the underlying assets – which relative benchmarking exacerbates.

As a result of this poor performance, the asset management industry is being increasingly criticised due to its lack of engagement with the corporations they are proxy owners of. John Kay in his review of UK equity markets argued that a large rise of non-UK owners has reduced the incentive to engage. The share ownership data published by Thomson Reuters shows that the majority of RBS shareholders were in fact UK domiciled, suggesting that this is unlikely to have had much impact. The top 15 owners of RBS shares collectively held almost 29%, the majority of which were UK domiciled funds. The story for Barclays was similar with share ownership slightly more concentrated with the top 15 owning 35%, the vast majority of which were also under UK management. A more relevant factor than the nationality of ownership is the fact that asset managers are already earning good profits from their existing business model. As a result there is less incentive to engage heavily on corporate governance issues.

It’s all in the charges

Income streams to asset managers are mainly derived from charges, which according to David Norman at TCF Investments, an asset management firm, can be up to a third of the investment returns generated. Hence institutional fund managers care less about improving absolute returns as their fees are not contingent on increasing absolute returns. This is further compounded by the fact that the majority of institutional fund managers are either index trackers or closet index trackers. Index tracking funds provide the market return to investors – hence traditionally they have been less engaged in corporate governance. Closet trackers, whose benchmarks are the same broad market indices, are more interested as to whether they beat the index or not rather than whether their clients earn absolute returns.

This suggests that the level of income streams arising from charges has been such that there has been little incentive to change the way in which fund managers interact with the companies that they “own”. However without an effective fund management sector, the information signals from the market will not be utilised, thus leading to the inefficient allocation of capital and poor returns to savers. One reason why these income streams are so high is the current opacity of charges levied by the industry, which makes it hard to understand what services savers are actually paying for and to compare effectively across providers. This is why mandating information disclosure to ensure the market functions more efficiently is crucial, as it will lead to falling charges and profits, thereby forcing asset managers to move up the value chain. Active managers, who are starting to see their fees erode (and profits) as the trend toward passive investment increases, have every reason to take account of market signals. Furthermore, there is no credible reason why tracker funds should ignore market signals either given that their profits would be higher if the absolute return of the market was higher. Indeed, it would be relatively straight forward to add a rule into an index fund that would automatically vote against any acquisition where the share price dropped by more than a certain percentage in the days following the announcement of a deal.

Until mandatory regulatory change on charges is implemented, it is less likely that fund managers will join the rest of the world in believing that markets do work. Markets provide a better synthesis of information at the company level than any individual can – as the acquisition of RBS demonstrated. The sooner the fund management sector recognises this, the sooner savers will see their returns begin to rise.