Preliminary estimates of the ex-ante natural rate of interest for 2013 – based on a credit disequilibrium framework – highlights positive profit growth for the United States. However, the ex-ante estimates for the United Kingdom imply a continued poor outlook for profits, mainly driven by the on-going challenges faced by its financial services sector.

Background

Setting the asset allocation for 2013 has been a tough process for investors. Following on from a decade-long period of poor returns, asset owners are still grappling with how to increase returns without exposing capital to unnecessary risk. The outlook for bond returns is unlikely to be stellar given yields are already low and may well begin to rise, thereby causing prices to fall. Although equity returns for 2012 were strong, it is unclear to investors whether this growth will continue or will in fact lead to another risk reversal causing capital destruction.

Many asset allocation strategies use a mixture of real GDP forecasts in conjunction with mean reversion frameworks to generate buy and sell signals. However, these approaches have generally failed to generate excess returns because they are based on a fundamentally flawed macroeconomic framework. These general equilibrium frameworks assume that by minimising fluctuations in output and inflation, the economy can be maintained close to its potential output, which can sustain asset price rises. Hence when an economy is above its equilibrium level, it is assumed that asset prices will fall or revert to their historical average. This approach therefore assumes that an economy oscillates around its equilibrium level through time.

Unfortunately this framework has not been of much help to investors with the vast bulk of funds being hit by massive losses in both the post dot com crash as well as the recent financial crisis. Clearly there are times when real GDP forecasts do coincide with rising profits and asset prices and mean reversion frameworks might work. However the fact that there is no correlation between GDP and equity returns should indicate to investors they are not sufficiently robust to use for investment signals. Moreover the recent analysis by Dimson, Marsh and Staunton in the 2013 Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook highlights that such market timing approaches based on mean reversion triggers are in fact less profitable than buy and hold.

Investment processes grounded in a general equilibrium framework fail to see turning points in the business cycle because this framework ignores the role of credit. Credit is of course one of the most important drivers of the modern economy with its ebb and flow causing most of its gyrations. Hence investors looking to time the market in order to avoid catastrophic falls in the value of capital ought to base their investment process on a macroeconomic framework that takes credit into account. Indeed credit-based macroeconomic frameworks can provide a great deal of insight into the general outlook for corporate earnings which has a more direct relationship with asset prices than real GDP growth. Moreover, these frameworks importantly do not assume any natural tendency towards equilibrium through time which is why business cycles are of different lengths and intensities.

The origins of credit-based frameworks go back to the great Swedish economist Knut Wicksell. He argued that what mattered for a credit economy was the relationship between the natural rate of interest and the money rate of interest. In modern terminology, this equates to the difference between the return on capital and the cost of capital at the macroeconomic level. When the return on capital is above the cost of capital, the excess profits drive credit growth fueling further rises in profits. More importantly Wicksell described a cumulative and dynamic process through time with the implications that credit bubbles will at some stage lead to a withdrawal of credit as expectations of increasing profits begin to fall. A more detailed explanation of Wicksell’s framework can be found in Profiting from Monetary Policy.

What does the data imply for 2013?

Estimations of the ex-post natural rate of interest are obviously highly correlated to corporate profits, and in most cases to asset prices. However, it is worth noting this is not always the case as during the dot com bubble profits were in fact falling and not rising. The ex-post estimates in table 1 show robust growth for Canada and the United States but only marginal growth for Japan in 2012. The absolute levels matter when it comes to profits which show Japanese companies are around 50% less effective in the way they allocate capital which is one of the reasons why the Japanese market has performed so poorly over the last decade. Finally it highlights the continuing poor performance of the United Kingdom which continues to be dragged down by the financial services sector. This is why the US equity market outperformed the UK market in 2012.

Table 1 Ex-post Natural rates of interest 2010 – 2012

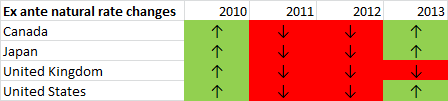

Such analyses are interesting but are clearly less helpful for investors given what is required are ex-ante estimates of profits. One of the realities of credit-based economic frameworks is that ex-ante rates change as new ex-post data becomes available. Hence the economy needs to be understood as a dynamic process that is constantly changing. Importantly ex-ante estimates do provide clear indications of rising or falling profit expectations which if followed would have avoided the dot boom and bust as well as signalling a shift into bonds in 2007. Such a preservation of capital would have been clearly invaluable for investors. However, there are times when the ex-ante estimates miss rising equity markets such as in 2012. Firstly firms tend to be more cautious in their outlook coming out of downturns and secondly exogenous factors that weren’t present at the start of the year can have a positive effect on profits too.

Table 2: Ex ante estimates

The ex-ante estimates for 2013 show a continuing positive outlook for profits in Canada, the United States and Japan, with the United Kingdom still in negative territory. The outlook for the United States has been boosted by the fall in consumer leverage. However Canada remains dangerously exposed to a reversal given its high level of consumer leverage although for now it appears to be resisting a shift towards negative profit expectations. Japan’s rate continues to rise, but its lower absolute level implies lower absolute returns. Finally the United Kingdom is still recovering from the massive slump in the financial services sector which has severely damaged profit growth across the economy. The data suggests that these pressures are easing but are not yet complete.

The other data set that needs to be taken into account is the cost of capital which in all four countries remains reasonably stable, although in the medium term it can be expected to rise rather than fall. As the cost of capital rises, it will require productivity growth to rise at a faster rate in order to sustain positive growth expectations. This is why long term forecasting is a rather pointless exercise. An economy is dynamic and constantly changing thus asset allocation needs to be constantly monitored.

Conclusion

The outlook for corporate profits at the macroeconomic level can be better understood by the extent and general trend of credit disequilibrium in an economy. The outlook for 2013 is positive for the United States with the United Kingdom still waiting to emerge from its financial services sector slump. Although the outlook for Japan and Canada is positive, the lower absolute level of returns on capital in Japan and the high levels of consumer leverage in Canada remain concerns. Finally, given that global equity prices are broadly correlated, with the United States making up around 25% of global market capitalisation, it can be expected that changes in the US index will have some impact on other markets.