A recent debate on the merits of NGDP targeting between Scott Sumner and Charles Goodhart has opened up an interesting discussion as to what bond investors should care about – inflation or the level of NGDP. Goodhart argued in the FT that the “likely implications of a dash for growth and the abandonment of an inflation target would at some point unhinge the government debt market.”

Sumner’s response to this point emphasises a fundamentally different perspective about what debt markets really care about. He stated that, “Goodhart is assuming debt markets care about inflation. They don’t. They care about NGDP growth.”

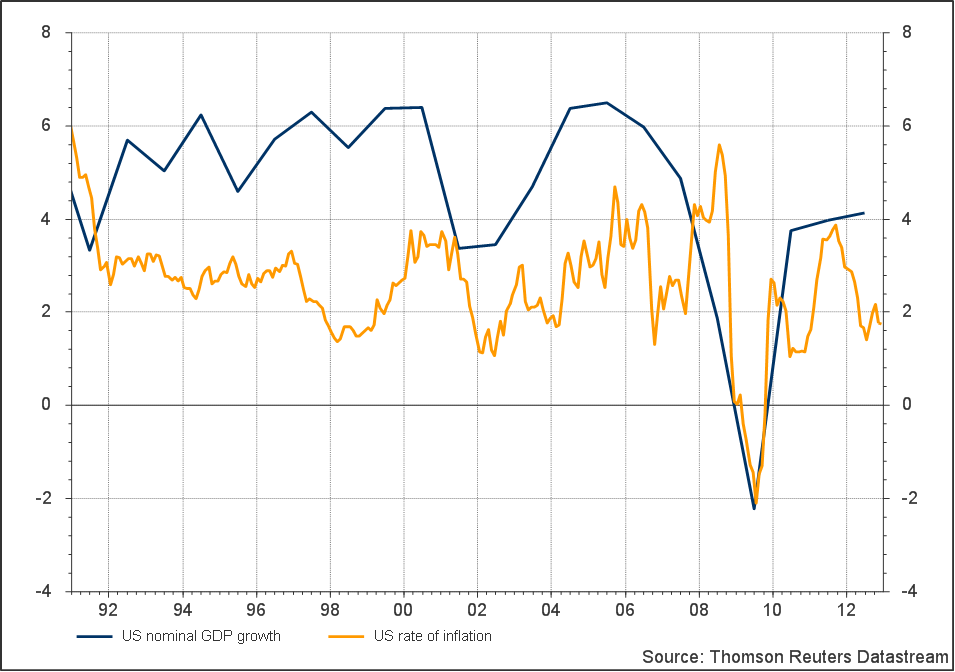

Sumner’s view that bond investors care more about NGDP than inflation is perhaps somewhat surprising given that bond market professionals are taught from day 1 in their careers that inflation is a bond’s worst enemy. Sumner argues persuasively that it is NGDP growth that causes higher inflation hence bond investors care more about the growth of NGDP. If inflation was only endogenously driven this would make sense and we would expect to see a strong positive correlation between the two factors demonstrating that as NGDP rises – signalling rising demand – so should inflation. However the chart below shows the relationship between NGDP and inflation has not been consistent since 1990, thus partially invalidating the endogenously driven view of inflation as espoused by Fisher, Friedman, Taylor and Sumner.

Although this relationship did hold during the 2000’s, there was an inverse correlation between the two series in the 1990s. The explanation behind this anomaly is that the general price level of the US economy was being deflated by the introduction of China and India into the global supply chain. In essence the 1990’s rise in NGDP was accompanied by falling inflation and falling interest rates. During the boom of the 1920’s, something similar took place where rising nominal GDP had limited impact on inflation which remained subdued leading to falling interest rates. These two episodes provide strong evidence that the general price level can also be exogenously determined, something that was always present in Bill Philips’ initial data set, but was conveniently ignored by monetary economists as a data anomaly. Unfortunately it is the data anomalies that more often than not end up explaining what is important for investors to take note of in order to generate positive returns. This is not to deny that inflation can be endogenously determined, it can, it’s just that investors who only focus on the level of NGDP will most likely miss the next structural shift in the economy. Hence understanding what is happening to the general price level still remains paramount for bond investors.