Although the returns on equities in the long run have been superior to those on bonds, equity returns remain extremely volatile due to the nature of the business cycle. Long-only investors attempting to minimise this volatility using indicators emanating from the current macroeconomic framework, have found this challenging. This is because the neo-classical framework is fundamentally flawed and generates misleading signals for investors. The post-crisis debate on reforming the financial system has largely ignored the fact that the neo-classical synthesis, which underpins monetary policy, is unable to model credit effectively. However, using the credit-based framework of Wicksell, which was later enhanced by Hayek and Myrdal, it is in fact possible to analyse the business cycle, thus allowing investors to switch out of equities before markets crash. This theory is based on the notion that differences between the return on capital and the cost of capital drives profits. The expectation of future profits in turn drives the process of credit expansion and contraction, which explains the business cycle. Thus aAnalysing the turning points of the business cycle thus allows investors to profit from a simple switching strategy between equities and bonds.

Equities still outperform in the long run but not over the last decade

Equity investors, according to the Barclays Capital Equity Gilt Study, have done well in the long run. Between 1925 and 2011, investors in US equities would have generated real returns of 6.6% pa despite five consecutive years of negative returns during the Great Depression. Bond investors would have fared less well with real returns of 2.6% pa. However, there is one main problem for equity investors, and that is equity returns can be extremely volatile. For example, anyone who had the luck of retiring in 1999 based on an equity portfolio started in 1960 would have generated returns of 7.7% pa, over 50% more per annum than the person who retired in 2008, which generated returns of only 5.1% pa.

Moreover, anyone who started saving for their retirement in 1999 and accepted the prevailing wisdom at the time that equities would maintain their upward trajectory, would have seen annualised losses of 0.9% pa. However, those who disregarded the consensus and invested in government bonds, would have seen annualised returns of 6.6%. Although the evidence is reasonably compelling in the long run to invest in equities, a ten-year period of negative returns on equities – which may be more than a quarter of the lifespan of an investment plan – is clearly a major issue for investors. Particularly given that when a person decides to start and stop saving for their retirement is partially out of their control. As of yet, however, there are few if any low-cost investment products that invest through the business cycle, generating equity-style returns with substantially lower volatility.

Today many investors use real GDP growth forecasts as a leading indicator of equity returns for asset allocation decisions, which is problematic for a variety of reasons. Firstly, real GDP growth forecasts failed to capture both the dotcom crash as well as the recent financial crisis. For those investors who were in equities during both those periods, by the time real GDP forecasts had adjusted, the market had already fallen, leading to substantial losses. This should perhaps not be surprising, given that the leading theorists of the current macro-economic paradigm have argued that events such as the recent financial crisis cannot be predicted, due to the inability of econometric models to identify structural shifts. Furthermore, investors have been duped since the 1980s by central bankers, who have consistently argued that as long as inflation remains subdued, an economy still has room to grow. The implication of the “spare capacity” argument is that the outlook for profits remains positive, thus asset prices ought to continue rising. The dotcom boom and recent US housing bubble both took place against a backdrop of low inflation, as did the Japanese property and equity bubble of the mid-1980s. These bubbles were missed because the neo-classical synthesis largely ignores credit. It is, of course, an expansion of credit – that may or may not lead to rising inflation – which causes sharp increases and subsequent falls in asset values.

Wicksell to the rescue?

One way of being able to construct such a low-cost fund that can generate equity-like returns with bond-like volatility, is to use a tactical asset allocation approach based on the credit theory of Knut Wicksell. The investment process is based on a straightforward annualised switching strategy between equities and bonds on a country basis. If we take US data from 1986 to the present, an equity investor would have generated annualised returns of 6.4% with bonds at 5.8% pa, so equities would still have been the better bet. However, the credit theory of Wicksell which was subsequently developed by Hayek and Myrdal – who jointly shared the 1974 Nobel Prize for Economics – does provide a great deal of insight into the trajectory of the profit rate and hence capital values. Indeed, investment triggers using this approach would have generated annualised returns of 8.2% with a lower volatility than that of bonds. It is worth noting that these returns have been inflated due to the strong performance of the bond market over the last 20 years, which is unlikely to repeat itself in the next 20. However equity-like returns with half the volatility are still an investment product with a great deal of value for consumers.

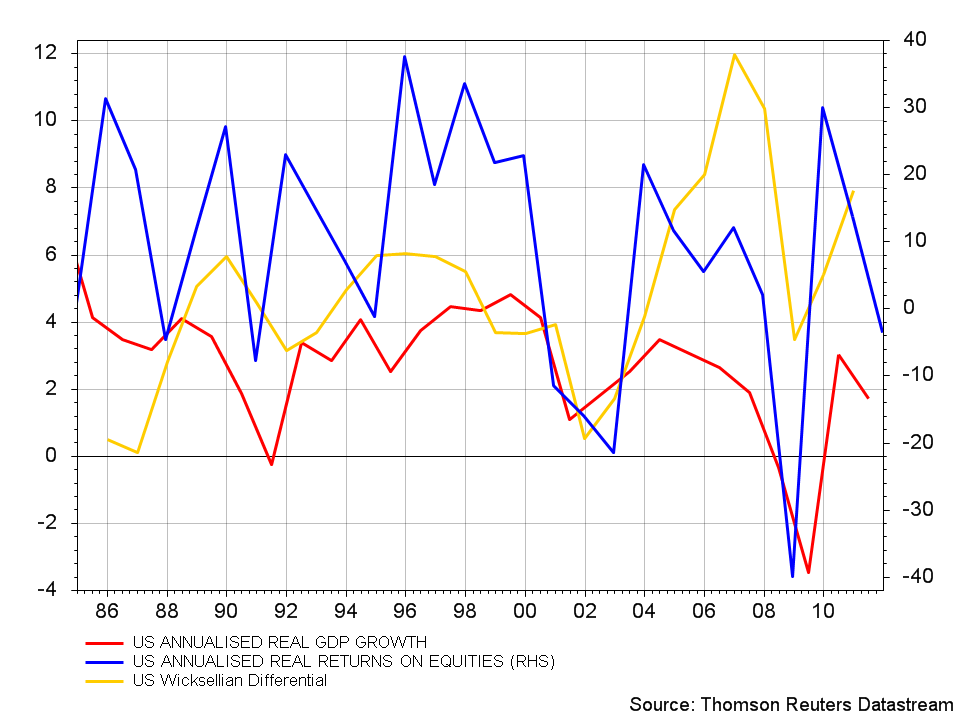

So how does Wicksell’s theory signal to switch to bonds before equity markets crash in value, thus avoiding the downside of equity price movements and switch back into equities when the outlook for profits improves? His theory is based on the notion that profits increase either due to an increase in the return on capital and/or a fall in the cost of capital. An improved outlook for profit growth stimulates credit creation, which in turn becomes critical to sustaining future profit growth. The Wicksellian Differential, which is the difference between the return on capital and the cost of capital, is thus an indicator of equity values. (For a more detailed understanding of how the Wicksellian Differential is calculated see Profiting from Monetary Policy, Infostream Q2 2011.) As shown in chart 1, Tthe relationship between real GDP growth and real equity returns, as shown in chart 1, is not particularly close except when output falls suddenly, thus providing further evidence that using real GDP as a signal is unhelpful for active equity investors looking to minimise the volatility of returns. Indeed, econometric tests have shown there to be little correlation between the two.

Chart 1 also highlights two interesting periods of the Wicksellian Differential and actual real GDP growth. Firstly from 1996, as the tech bubble kicked off, the rate of profit growth began to decline, although real GDP growth and equities rose until they crashed, resulting in losses of trillions of dollars. This is one of the reasons why the returns to this investment strategy are less volatile. The second period was in 2004-2006, when the rate of profit growth was rising as were equities, despite real GDP growth being in decline. The rate of profit began to decline in 2007, thus indicating a switch to bonds, but allowing investors to capitalise on the increase in capital values between 2004 and 2006.

Chart 1: US real GDP growth, real equity returns and Wicksellian Differential

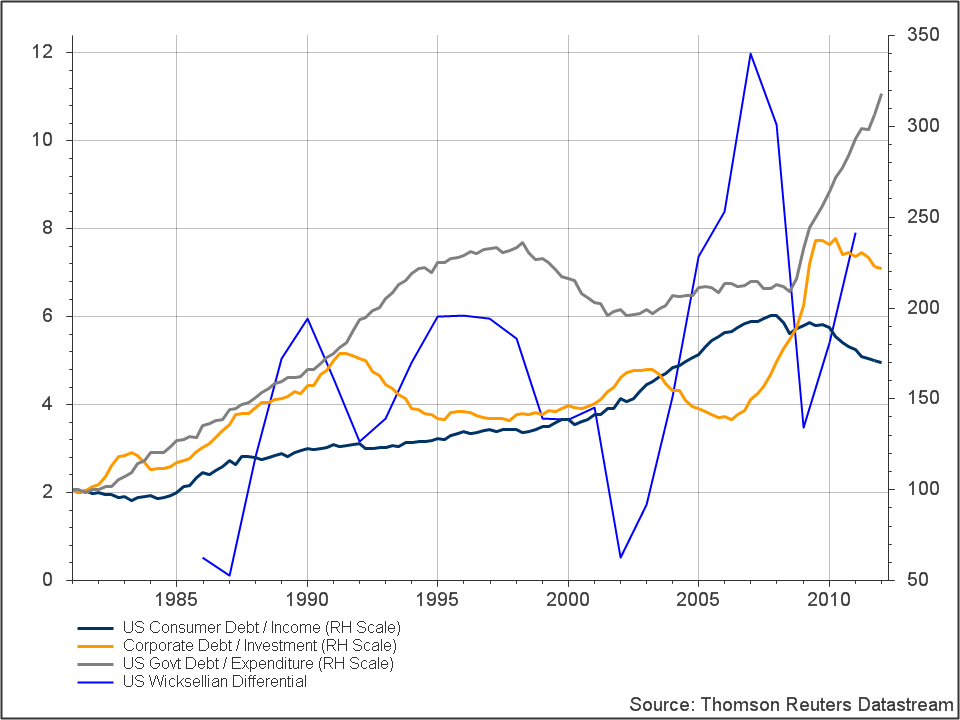

The calculation of the Wicksellian Differential is however an ex-post measure, so is unhelpful for investors to use as an investment trigger, hence an ex-ante model needs to be constructed based on the underlying drivers of growth in the Wicksellian Differential, which is of course leverage. However, an ever-increasing amount of leverage is clearly unsustainable and will cause expectations to shift at some point, resulting in a period of deleveraging and falling profits. As a result, an investment trigger can be set up based on the dynamic relationship between leverage ratios and the rate of profit, which requires constant recalibration as new data is made available.

Borrow, borrow, borrow… Default

Chart 2 shows three leverage ratios – consumer, corporate and government against the Wicksellian Differential highlighting the key drivers of rising and falling profits. The relationship between each leverage ratio and the rate of profit is unique and dynamic through time. For example, the slowdown and fall in the consumer leverage ratio caused the Wicksellian Differential to reverse between 1990 and 1992. Furthermore, during the tech bubble between 1996 and 1999, corporate leverage fell followed by consumer leverage, causing the rate of profit to fall. This highlights that there was no real basis for rising equity returns during the tech bubble as the rate of profit growth was falling. Thus the dotcom bubble ought to be seen as akin to John Law’s South Sea bubble, which was purely based on a rather large misconception. The extent of the credit bubble leading up to the recent financial crisis is highlighted by the substantial rise in consumer leverage, the rate of which began falling at the end of 2006, highlighting the downturn in the rate of profit growth in 2007, and thus a shift to bonds. Finally consumer leverage rose again in 2009, signalling a recovery in profits, although the recovery was short-lived. In 2011 the trend fell again, and the 2012 signal highlights a continuing slowdown in the underlying trend of profit growth.

Chart 2: US leverage ratios vs Wicksellian Differential

There are of course other factors that impact profits, such as significant changes in the general price level and in output per worker, as well as other known variables such as the tax rate; however, the most important driver with respect to the turning points is the realisation that a period of credit expansion has become unsustainable, leading to changing expectations.

Conclusion

Current attempts by regulators to prevent another crisis – although well meaning – are unlikely to result in an end to the business cycle. Innovation will continue to drive new opportunities to generate profits, and the subsequent demand for credit to increase investment will be met by the constant innovation of the financial services sector. Investors therefore need to protect themselves from future volatility, given the timing of the next boom and bust is unknown. The cheapest and simplest way of doing this is to switch between equities and bonds triggered by changes in the underlying profit trend. In his excellent FT blog Willem Buiter, now Chief Economist at Citigroup, wrote that since the 1970s most developments in economic theory which underpins much of the current understanding of the way an economy functions have been a waste of time, focusing on the internal logic of problems rather than a desire to understand how an economy works. As a result investors using the neo-classical framework have too often been on the receiving end of large and unexpected losses.

Nothing in this commentary is a recommendation to buy, sell or hold any security.

Further Reading:

Aubrey T, Profiting from Monetary Policy, Infostream Q2 2011

Barclays Capital Equity Gilt Study 2012

Buiter W, The unfortunate uselessness of most ‘state of the art’ academic monetary economics 2009 www.ft.com

Hayek F, Monetary Theory and the Trade Cycle 1929

IMF Global Financial Stability Report, September 2011

Lucas R, Econometric Policy Evaluation; A Critique 1976

Lucas R, In defence of the dismal science 2009 www.economist.com

Myrdal G, Monetary Equilibrium 1939

Ritter J, Economic Growth and Equity Returns 2004

Wicksell K, Interest and Prices 1898